|

Zenobia Embry-Nimmer -- poor's voice

- Kevin Fagan, Chronicle Staff Writer

Tuesday, September 13, 2005

It was raining and bitterly cold on the morning Zenobia Embry-Nimmer stepped

into a half-constructed house in East Oakland to find street minister Henry

Robinson dying on his couch, kitchen stove burners cranked up high in a vain

attempt to ward off the chill. Ms. Embry-Nimmer had heard her old friend had

AIDS, and on this rainy day when she found it was true -- and that nobody was

helping -- fury filled her face.

"This is so very, very wrong, and, by God, I'm going to do something about

it," she seethed, stomping away from the house.

That was in December 1991. In short order, Robinson was placed in a hospital

with round-the-clock care -- and when he died a month later, he did so with

dignity, instead of shivering in his house alone. "Zenobia is an angel," he

whispered to a reporter a day before his death.

A lot of people thought that of Ms. Embry-Nimmer, one of the most ardent

advocates for the poor and homeless in Alameda County for the past two

decades. When her time came to die Monday at 1:45 a.m. at Summit Hospital in

Oakland, at age 57 after a two-year battle with cancer, they couldn't find

enough adjectives to describe her.

"She was a warrior in the truest sense," said Boona Cheema, executive director

of the Berkeley-based nonprofit Building Opportunities for Self-Sufficiency.

"In moments like now, after Hurricane Katrina, is when her spirit comes forth

for me -- you know, to speak the truth. That's what she did extremely well, no

matter how influential the people were who she was talking to."

Ms. Embry-Nimmer was perhaps best known as the executive director of the

Emergency Services Network from 1989 to 1993, an organization routing the

resources of nearly 200 poverty-aid agencies in Alameda County. When the 1989

Loma Prieta earthquake shattered more than 1,000 units of low-income housing

in the county, Ms. Embry-Nimmer was in a key position to push for it to be

rebuilt with governmental disaster aid -- and she did so with a vengeance,

becoming the best-known voice for the poor, the homeless and their housing

needs.

In the end, millions of dollars, including $10 million from the Federal

Emergency Management Agency, went into replacing the units with double the

numbers that were there before.

"She was a tireless fighter for individuals who in most cases didn't have a

public voice to go to decisionmakers," said Alameda County Board of

Supervisors Chairman Keith Carson, who during the quake was an aide to then-

Rep. Ron Dellums, D-Oakland. "She was consistent and articulate and to the

point as their spokesperson, and even if it made policymakers uncomfortable,

she made us take in the information."

One of her chief skills was that she was equally at home with the poor and in

the halls of power.

"Zenobia felt extremely comfortable around people in the street, who felt

angry -- but she also had a background of being educated and knowing how to

approach government," Carson said. "She was unique that way."

Former Oakland Mayor Elihu Harris remembered Ms. Embry-Nimmer being especially

adamant about the creation of Oakland's Henry Robinson Multi-Service Center,

which opened in 1993 in memory of her street-preaching friend and offers the

homeless everything from housing to job counseling.

"One reason we don't have the problem with homelessness in Oakland that you

see in San Francisco is because of that center," Harris said. "Now, I wonder

who will be inspired to take up the baton after she is gone?"

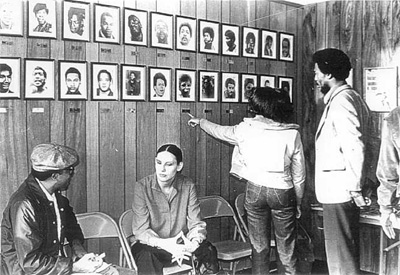

Zenobia sitting in chair at the BPP Central HQ in 1977

Ms. Embry-Nimmer was born in Emporia, Kan., to Robert and Katherine Embry. She

recalled in the book, "Black, White, Other," by Lise Funderburg, seeing a

black man burned to death when she was 8 -- and that experience, combined with

being homeless herself in the Bay Area for two years after moving here in

1967, ignited her life's passion.

"How can anyone walk by and not help?" she told a reporter, eyes moist, while

walking through Loma Prieta rubble passing out food to the homeless.

Ms. Embry-Nimmer earned a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University

Without Walls in the early 1970s and over the next two decades became a

counselor or director at several Bay Area agencies aiding substance abusers or

the impoverished, including the Drug Awareness Program and Upward Bound. Proud

of her mixed Cherokee and African American heritage, she was also active in

Native American and black organizations, including helping re-form the Black

Panther Party in the 1990s.

"She loved to say that when she was a kid and watched cowboy and Indian

movies, she always rooted for the Indians," said her husband of 27 years,

Richard Nimmer.

After leading the Emergency Services Network, Ms. Embry-Nimmer was a director

at Satellite Senior Homes, Dignity Housing West and the Workforce Development

Collaborative. In 2003 she was diagnosed with cancer and quit working to try

to beat the disease at home in Oakland.

"She made most people she knew into better people, right up to the end," said

Richard Nimmer.

In addition to her husband and her parents, Ms. Embry-Nimmer is survived by

two daughters, Lynn Marie Embry-Nimmer of Northridge (Los Angeles County) and

Michelle Smith of Los Angeles; a sister, Lynn Marie Barnes of Alaska; and a

brother, Robert Embry of Antioch.

Memorial services are pending.

Page B - 5

URL:

sfgate.com/cgi-bin/article.cgi?file=/chronicle/archive/2005/09/13/BAGP6EMNMV1.DTL

|